A TACTICAL ANALYSIS OF MANCHESTER CITY: GUARDIOLA'S POSITION, PASS AND POSSESSION MANTRA

Pep Guardiola is arguably one of the most decorated and revered managers in the history of football. He’s appreciated and celebrated for his silky and breathtaking brand of football, although there have been times when perhaps he’s looked too clever for his own good.

Despite two outstanding seasons between 2017 and 2019, where his men accumulated 198 points across two Premier League campaigns and won every domestic trophy out there to win, the UEFA Champions League is the one that has slipped between Guardiola’s fingers every single season since 2011. Since his appointment in 2016, the Cityzens have failed to reach the Champions League semi-final stages on four different attempts, losing out to teams like AS Monaco, Lyon, and Tottenham Hotspur – teams they’d otherwise be expected to beat.

Major Questions

In the 2019-20 season, Manchester City looked a shadow of the team they used to be. Their captain, Vincent Kompany, left the club after serving 11 years and was not replaced, Leroy Sané suffered a cruciate ligament injury in the FA Community Shield match that ruled him out for the rest of the season, and Aymeric Laporte too had to sit out the entirety of the season with a knee injury. All this compounded to Pep’s worst season as City’s manager.

The 2020-21 season started in a similar manner as the City back-line fluffed its lines time and again. An embarrassing 2-5 home defeat to Leicester City was the final straw, as two days later City completed the £61m signing of Rúben Dias from SL Benfica. The centre-back pairing somewhat stabilised with Dias and Laporte, but the personnel at the fullback positions and the domino effect at the centre of the midfield was evident as it lacked cohesion and substance.

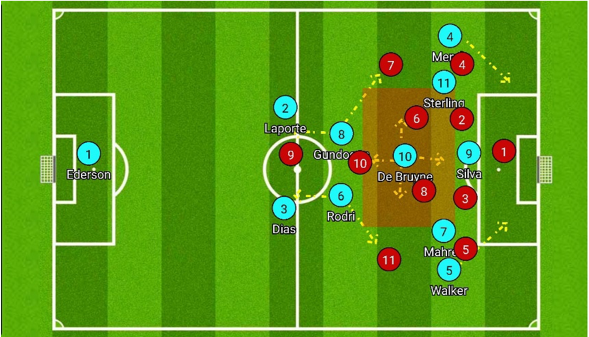

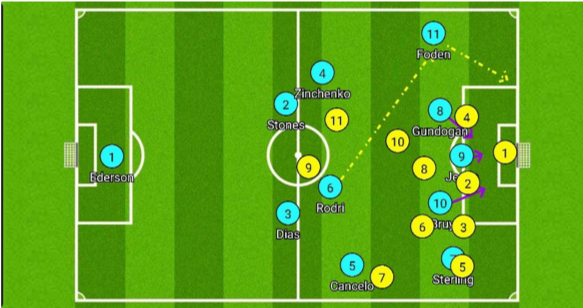

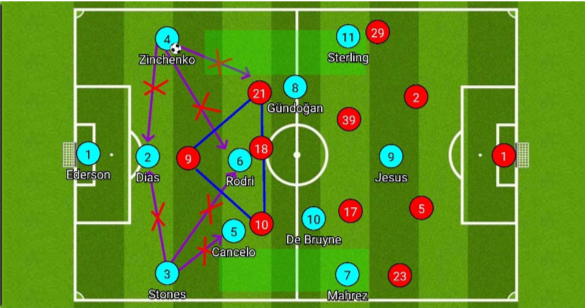

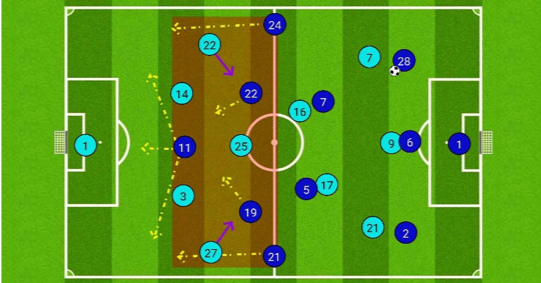

Start of 20/21 season with wingers cutting in and fullbacks bombing forward.

Start of 20/21 season with wingers cutting in and fullbacks bombing forward.

Benjamin Mendy is a natural fullback who hugs the touchline and bombs forward to make overlapping runs, while Kyle Walker on the other side is more inverted but is very conservative on the ball. With the fullbacks joining the final third in attack, that left ?lkay Gündo?an to cover the space left behind Mendy while Rodri sat alongside him to negate any potential counterattacks as seen below.

City Forwards and Midfielders in their designated roles.

City Forwards and Midfielders in their designated roles.

With the fullbacks trying to whip balls in from far wide or making a run to the byline to cut balls inside, the forwards would take up the half-spaces between the opposition centre-backs and fullbacks, as can be seen with Riyad Mahrez and Raheem Sterling’s position in the above picture.

But that had problems of its own, as Gündo?an’s positioning of more of a double pivot with Rodri left Kevin De Bruyne as the lone creative outlet, which can easily be negated with a 2v1 scenario by overloading the half-spaces in front of him. Any counterattack during transitions ultimately led to City committing mistakes and conceding goals with Gündo?an and Rodri lacking pace and the opposition forwards outnumbering them in the ensuing 4v5 situations.

The New System

By the Christmas period, City were languishing in eighth place, having amassed only a total of 23 points from 13 games and sitting 11 points behind then leaders Liverpool. Then came the tactical switch that reinvigorated City’s season. Though City still played with a 4-3-3 on paper, their formation became more of a 2-3-5 in attack – almost a tribute act to the 2-3-5 Pyramid systems of the late nineteenth century.

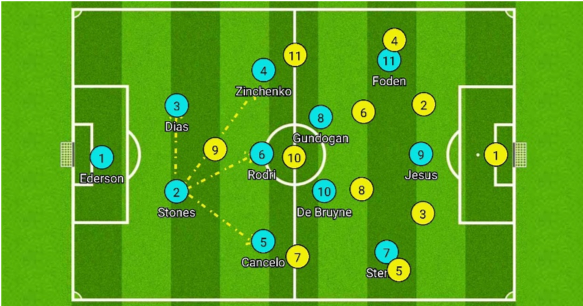

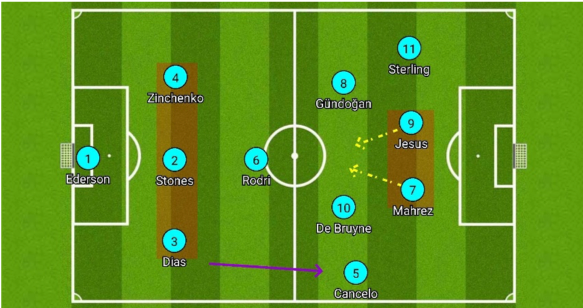

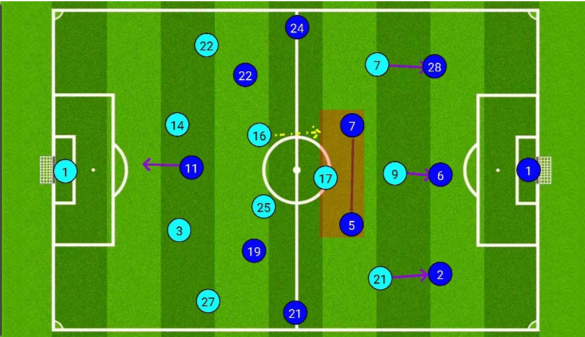

The 2-3-5 approach

The 2-3-5 approach

In this new system, the wingers would hug the touchline on their favoured sides and cut in balls instead of whipping them in, while the fullbacks tucked in into the second line of defence and recycle the possession. Many teams have used this system, mainly in possession, but most notably it was Guardiola’s Barcelona side that used the system more consistently, though instead of wingers, Pep had fullbacks (Dani Alves and Maxwell) bobbing up and joining the attack in the final third.

Pep’s Man City is the closest anyone has come to revive that 2-3-5 system, with Sterling and Phil Foden performing the wide-winger roles and fullbacks Zinchenko and João Cancelo drifting inwards as more of a buffer in front of the backline of Rúben Dias and John Stones.

Defensive Solidity

The key is the shielding at the centre as shown above.

The key is the shielding at the centre as shown above.

Guardiola has time and again emphasised the importance of positional play and the intricacies of link-up play. These changes allowed City to overload the middle of the park with Gabriel Jesus dropping deep, which let the free number 8s Gündo?an and De Bruyne to take up the half-spaces left behind him. The aim was to pass the opponent out of the game, with Rodri taking up more of a ‘centre-half’ role, allowing the centre-backs to drift wider and make it a back-three during counterattacks.

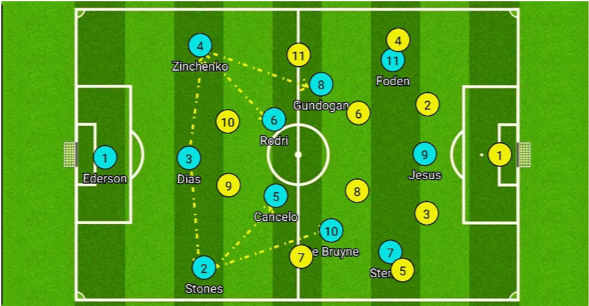

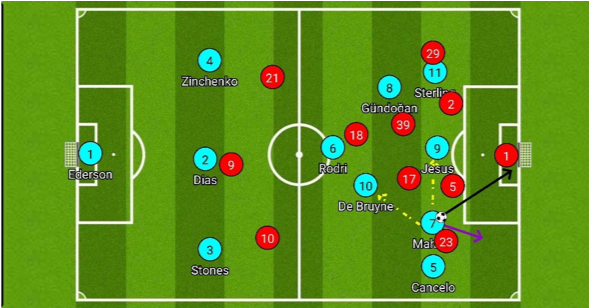

The change in build-up approach

The change in build-up approach

The change in personnel also changed the approach of their build-up play. When facing a low block the two fullbacks would drift inwards, creating a 2-3-2-3 setup, which gave the centre-backs more angles to pierce the first line of attack and free up the two number 8s to join the forward line. The system tweaked itself, though, when coming up against a high-pressing team as shown in the figure below.

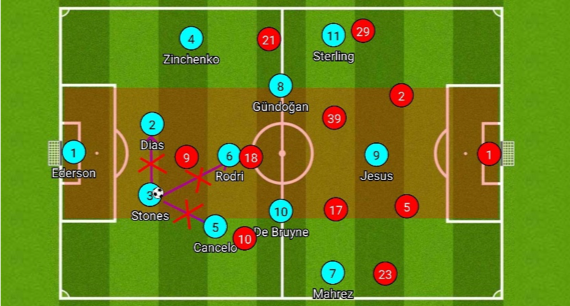

Build-up play when facing a high-pressing team

Build-up play when facing a high-pressing team

Under high pressure, Zinchenko would drop back into a left-sided centre-back role, while Stones drifted to the other side to create better angles to break the first press and move the ball into the vacant spaces at the middle of the pitch. All of this became possible due to Zinchenko and Cancelo’s composure on the ball and their ball progression, which Mendy and Walker both lack. While Mendy would stay wide and make overlapping runs, when Walker moved into these positions, he would remain more static than the other three.

Attacking Prowess

The inclusion of Zinchenko and Cancelo unlocked City’s midfield as the free number 8s in Gündo?an and De Bruyne gained more offensive duties than defensive ones. With the fullbacks tucking in and Rodri taking the centre-half role, Gündo?an and De Bruyne were able to drift wide and link up with the likes of Foden and Sterling.

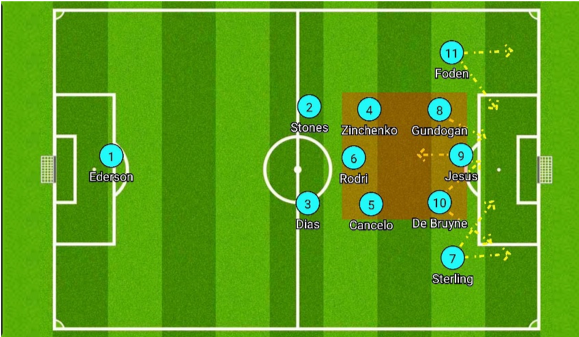

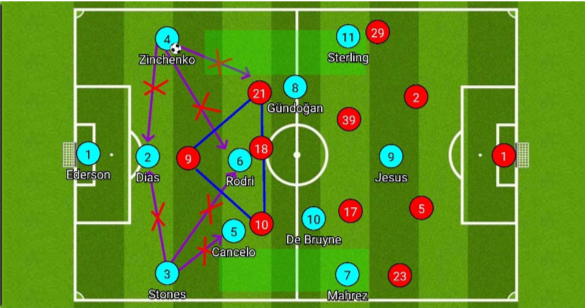

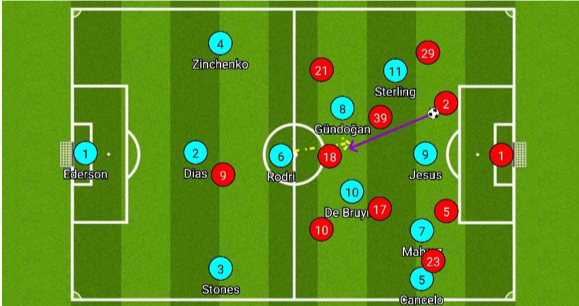

Movement of City’s forward line

Movement of City’s forward line

With Jesus dropping deep, De Bruyne and Gündo?an could take up the half-spaces while also drifting wide and interchanging with the wingers to break the opponent’s defensive structure. The results were there for all to see, as Gündo?an enjoyed one of his best seasons in front of goal and De Bruyne racked up assists and pre-assisting for most of City’s goals.

The role of the shielding trio cannot be underestimated though. Zinchenko and Cancelo would often drift wide but not forward, just enough to create an overload in the flanks. The result was an out ball to the other flank, where the winger cut in balls across the six-yard box, with runners like Gündo?an, De Bruyne and Jesus all waiting to pass the ball into the back of the net.

City’s effective switch of play

City’s effective switch of play

Cancelo or Walker?

Kyle Walker has been an integral part of this Manchester City side, playing key roles in their back-to-back Premier League title wins. In those seasons, Pep had two creative outlets in David Silva and Kevin De Bruyne, which allowed Walker to invert into the midfield and take up spaces created by the attackers in front of him.

João Cancelo, on the other hand, came from Juventus and had to be Walker’s understudy for the 19/20 season. The Portuguese fullback came with the reputation of possessing attacking flair but lacked defensive stability, which raised a few eyebrows when City signed him for £60m with Danilo going the other way for £32m. While both Cancelo and Walker can play inverted fullback role from the right, they possess different characteristics both on and off the ball.

Cancelo pushing higher up so that Mahrez can be the second false 9.

Cancelo pushing higher up so that Mahrez can be the second false 9.

When playing with two inside-forwards on both flanks, Cancelo pushed up the pitch, while Zinchenko dropped deeper to make it a back-three. With Cancelo higher up on the right flank, Mahrez could drift inside and make it a double false 9 in the middle of the pitch, where either of the two could drop deep to link up the play while still having an extra forward up top.

Now, let’s dive a little deeper to assess a situation where the right-back would slot into the midfield. When Pep started Kyle Walker in that role, the Englishman would slot in beside Rodri but played short and safe passes closer to his range, or in extreme cases a switch of flanks. With David Silva that approach justified, as it meant the Spaniard and De Bruyne could run the show from the middle of the park.

Walker’s distribution and positioning

Walker’s distribution and positioning

Walker would tend to drift wider to tackle any potential counterattack, or push a bit higher to create the overload, but rarely joined the attack in the middle of the pitch which limited the free number 8s from drifting wider and interchanging with the wingers. Cancelo, on the other hand, is a two-footed fullback and has a wide range of passes in his arsenal. While doing all the things that Walker could, Cancelo possesses more composure on the ball and can carry the ball forwards in between the lines.

Cancelo’s distribution and positioning

Cancelo’s distribution and positioning

Last season, Cancelo created 2.87 shot-creating actions, completed 2.57 dribbles and had 8.67 progressive carries per 90. Though his trickery on the ball would land him in vulnerable situations at times, for all his reputation of lacking defensive abilities, Cancelo averaged 3.0 successful tackles and 1.92 interceptions per match – an almost 40 percent improvement on his performances from the season before and, more importantly, miles clear of Walker in that same role.

A new approach, but same results?

Pep Guardiola has always been someone who saves all his experiments for the bigger occasions. After winning 22 matches on the bounce, City squared off against their neighbours. With City more or less running away with the title, it was a battle for bragging rights in this Manchester derby.

United overloading the centre of the pitch

United overloading the centre of the pitch

Pep seemed to have formulated a plan to overload the middle of the pitch, with the wingers in more of an inside-forward role and the free number 8s taking up the half-spaces in between the lines. But Ole Gunnar Solskjær and his men had other ideas. Right from kick-off, the United players were on the City defence like a rash, which earned them a penalty just 33 seconds into the match to take the lead inside two minutes.

Despite that, United pressed the City defence higher up the pitch, with Marcus Rashford and Bruno Fernandes man-marking Rodri and Cancelo while Anthony Martial kept the centre-backs on their heels. The City defence was left with no outball to bypass the first press and build up their play from the back.

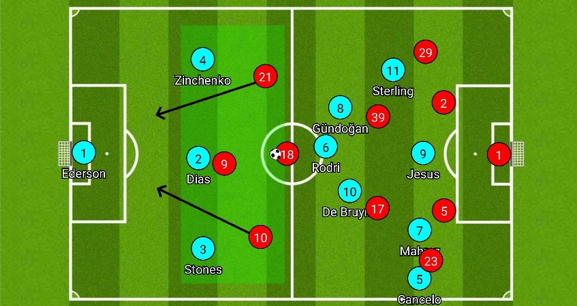

Stones and Zinchenko drifting wide to create gaps

Stones and Zinchenko drifting wide to create gaps

For that reason, John Stones and Zinchenko drifted out to the flanks to make it a wide back-three, giving a better angle to Ederson and Dias to play out from the back. But the triangle created by United’s front four meant it took out at least five City players in the middle of the pitch, leaving only the flanks to progress the ball. And since United took the lead on the very first minute of the game, this setup played perfectly into their hands.

City in the final third vs United

City in the final third vs United

When they did get the ball forward, with Mahrez and Sterling drifting inside, Gündo?an moved slightly wider to interchange with Sterling on the left side, while De Bruyne dropped deeper in a traditional number 10 role. In the above picture, Mahrez is on the ball from where he could take a shot or lay it off to Cancelo to whip in a cross from the byline. Of the other two options, Jesus was at all times surrounded by 2-3 United players, while De Bruyne’s free role was cancelled out with Man Utd’s narrow approach and their man-marking on the other City players.

City losing the ball in central areas

City losing the ball in central areas

City repeatedly lost the ball near the United 18-yard box, which can be seen in the above picture. When Harry Maguire or Victor Lindelöf had the ball at their feet, the easy outball was always in front of them in the shape of Bruno Fernandes. With Gündo?an and De Bruyne assigned with more offensive duties, Rodri was given the role of cutting out those outballs and recycling the possession.

Rodri’s missed interception led to a 3v4 situation.

Rodri’s missed interception led to a 3v4 situation.

But on occasions where the City midfielder did mistime his interceptions, it presented United with a 3v4 opportunity on the break. With the pace of Rashford and Daniel James, the City centre-backs couldn’t commit to their man and had to back off to somewhat slow them down. United hurt them time and again before finally sealing the victory in a similar fashion, with Luke Shaw slotting home a cutback and coming out deserved winners with a 2-0 victory.

Not the finished article

Though City managed to turn around their dismal start to one of resurrection, their system was not a bulletproof one, as shown by Chelsea in their FA Cup semi-final triumph and their league win a few weeks later.

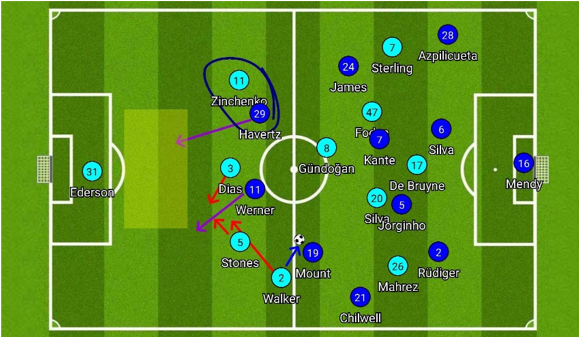

Let’s take their FA Cup win for reference. Right from kick-off Tomas Tuchel used a lopsided approach with Thiago Silva and Antonio Rüdiger dropping deep to collect the ball, drawing pressure from City’s front three. César Azpilicueta stayed out to be the easy outlet and when the ball did go out to him, Sterling moved in to press resulting in an easy outball to N’Golo Kanté.

Raheem Sterling wouldn’t have been higher if Benjamin Mendy closed down Reece James, which would have allowed an easy ball to Hakim Ziyech in behind Mendy. Chelsea looked to push their wing-backs up, but rather than keeping their wingers close to the wing-backs, City had them narrow, closing down on the centre-backs, with De Bruyne left to tie up the double pivot of Kanté and Jorginho.

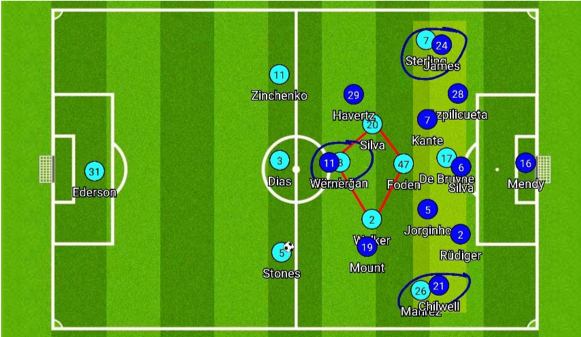

City wingers pressing the Chelsea backline.

City wingers pressing the Chelsea backline.

This double pivot allowed the Blues to bypass the City press and build up their play with either Kanté or Jorginho dropping deep to collect the ball. But this was a major problem for City, because when this front-four press was isolated it gave them a 6v5 advantage in the defensive areas but they’d lose control of the midfield. To stop that outball to the pivots, Rodri moved up to counter that ball, leaving Fernandinho as the lone pivot and a 5v5 situation emerged.

At times Ziyech or Mason Mount would drop deep into these half-spaces in the middle of the pitch and receive the ball in between the lines, causing a lot of problems as the pace of Timo Werner meant that the centre-backs couldn’t commit to these half-spaces. With City’s narrow approach, Tuchel smelled blood as he exploited the flanks repeatedly. When a wing-back looked to receive the ball deeper, City’s fullbacks pressed high, leaving acres of space behind them for the Chelsea forward line to run into.

Chelsea forwards enjoying the spaces left by City fullbacks.

Chelsea forwards enjoying the spaces left by City fullbacks.

Pep would have sensed this earlier as he put two pivots in his midfield, who would track the run of the Chelsea forwards running on these open spaces. But the flaw in the system was evident as it meant Chelsea could switch their play at will, from the wings to centrally and vice versa. This was clearer with their goal; as Cancelo pressed on Ben Chilwell, Mount took the half-space left behind him and played a measured through ball for Timo Werner to run behind, which the City defenders had no answer to. Ziyech took up the space left behind Mendy and slotted home Werner’s pass to win the game for his team.

‘Tinkerman’ costs City again

Manchester City bowed out of the Champions League final with a whimper, a match perhaps won on the touchline, rather than the pitch. The seeds of Manchester City’s meek defeat lie at the door of Pep Guardiola and his overthinking.

Again.

Guardiola’s decision to switch to an unfamiliar 3-4-3 formation and reduce his side’s creative output in attacking areas backfired as Chelsea ran out 1-0 winners thanks to a Kai Havertz goal. Guardiola dropped the first bombshell when the starting lineup came out, a midfield trio of Silva, Foden, and Gündo?an – no pivot – in a Champions League final.

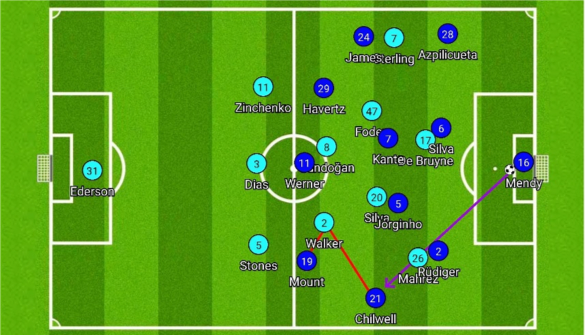

Guardiola’s men had the lion’s share of possession, which had been the case throughout the season. As the teams were getting a feel of each other, it was Walker who was bobbing up during the early exchanges and tried to link up with Mahrez. With the teams settling down, Walker drifted inside to create a diamond in the middle – Guardiola’s attempt at overloading the midfield.

City’s diamond in the middle of the pitch

City’s diamond in the middle of the pitch

But, unlike their previous two encounters, Chelsea’s wide centre-backs and the pivot of Jorginho and N’Golo Kanté dropped deeper to cover any half-spaces, while Timo Werner clung onto Gündo?an like a leech. With both their wingers getting man-marked from the very first minute and their most creative outlet getting wasted up top, the diamond only added to their misery as it meant the ball could only be recycled in the second phase of the play without ever troubling Chelsea’s final third.

And so it proved to be, as City had 60 percent possession but only attempted seven shots, with one on target and an xG of 0.52. Tuchel, on the other hand, was happy to start cautious as his team grew into the game.

Chelsea exploiting their left flank

Chelsea exploiting their left flank

Chelsea initially looked to build up from the right side and pick out Havertz aerially, as the German had a clear height advantage on Zinchenko. But the Ukrainian held his own as he won five out of the seven aerial duels, while Sterling’s high pressing on Azpilicueta meant Chelsea had to look for other alternatives, with his shadow cutting off channels to Reece James further up the pitch.

With the right side cut off, Chelsea saw opportunities on the left as Mahrez’s aggressive pressing on Rüdiger left Chilwell in the open, creating a dilemma for Walker. The England international now had a decision to make, with Chilwell in front of him and Mount running in behind.

Walker pressing high up leading to Chelsea goal

And then came the sucker punch. Mendy’s ball found Chilwell in open space, bypassing City’s first line of defence. Walker then committed the grave mistake of pressing high on Chilwell, leaving Mount free with runners in front of him. When the English right-back did recover, he ran to cover Werner’s run instead of closing down Mount’s angle. John Stones was already having a jittery afternoon, and when Werner darted his run on the outside, the City centre-back rushed to cover him, leaving Dias no other choice but to drift wider to maintain the width.

It left three City defenders covering one Chelsea player, while Havertz only had Zinchenko to beat in a battle of foot race. Mount pinged in a delicious ball, ripping through the heart of the City defence, and Havertz met the ball just in time to round off Ederson and slot home the winning goal. City lost De Bruyne on the hour mark; the Belgian collided with Rüdiger resulting in multiple facial fractures. Gabriel Jesus replaced the City captain, with Guardiola looking for added firepower up top.

But it was Fernandinho’s introduction in the 64th minute that highlighted Pep’s glaring mistake. All of a sudden, City’s midfield looked more assured, more composed, both on and off the ball. They recycled possession well, intercepted balls better, the whole shebang. City huffed and puffed, but Chelsea’s defence stayed resolute. N’Golo Kanté, in particular, produced one of the most complete performances in a Champions League final. The Frenchman was everywhere, intercepting balls, making last-ditch tackles, bursting pace, making line breaking runs, joining the final third in counterattacks – the most complete performance.

For a team that once flirted with the proposition of completing the improbable quadruple, the UCL final defeat will be a bitter pill to swallow. Pep’s quest for that elusive third Champions League title drags on for another year, and as mentioned in the beginning, Guardiola’s genius and obsession with the game can, at times, be too clever for his own good.

Written By

Rahul Saha