How Graham Potter’s tactical flexibility could shape Chelsea in the long run

The 2021/22 season was a massive success for Brighton & Hove Albion as they scored the most points and secured a top-half finish for the first time in the Premier League. Although numerous contributions—both on and off the pitch—have made this success achievable, much of the credit has to go to their now-former manager Graham Potter, who moulded the Seagulls into a highly possessional and positionally-adept side, even when they played against the league’s best teams.

The most striking characteristic of Potter’s Brighton lay in their flexibility of systems both in and out of possession using different tactics and formations every other week. According to a report published by the Premier League at the end of the 2021/22 season, Brighton were responsible for using the most systems (13) throughout the season, cementing themselves as the most fluid team in the league.

This article will focus on Potter’s structure in possession, divided into three sections of play — build-up play, progression, and the final third — examining how it can, both in the short and long terms, shape Chelsea with Potter at the helm.

Also Read – Manchester United: How to fail successfully

Build-up play

Adaptability of the backline

Regardless of the different ways in which the opposition would set up and the various ways they would have devised to face them, Brighton would always look to build play from the back under Potter, with their goalkeeper Robert Sanchéz playing a crucial role.

This allowed the Seagulls to lure the opposition players out of their structural position, creating holes within the defensive setup to create progressive passing channels — whether that’s going through, around, or over the opposition’s pressing structure.

However, in order for this to be successful, the system must offer safe passing options to the goalkeeper. But how does a system provide these passing options?

Well, the defenders providing this support would not only position themselves deep but wide up to the width of the 18-yard-box—or even wider—to expand the defensive structure and open passing lanes further up the pitch. However, what gave them superiority over the opponent’s first line of pressure is the adaptability of the entire back line, including the goalkeeper.

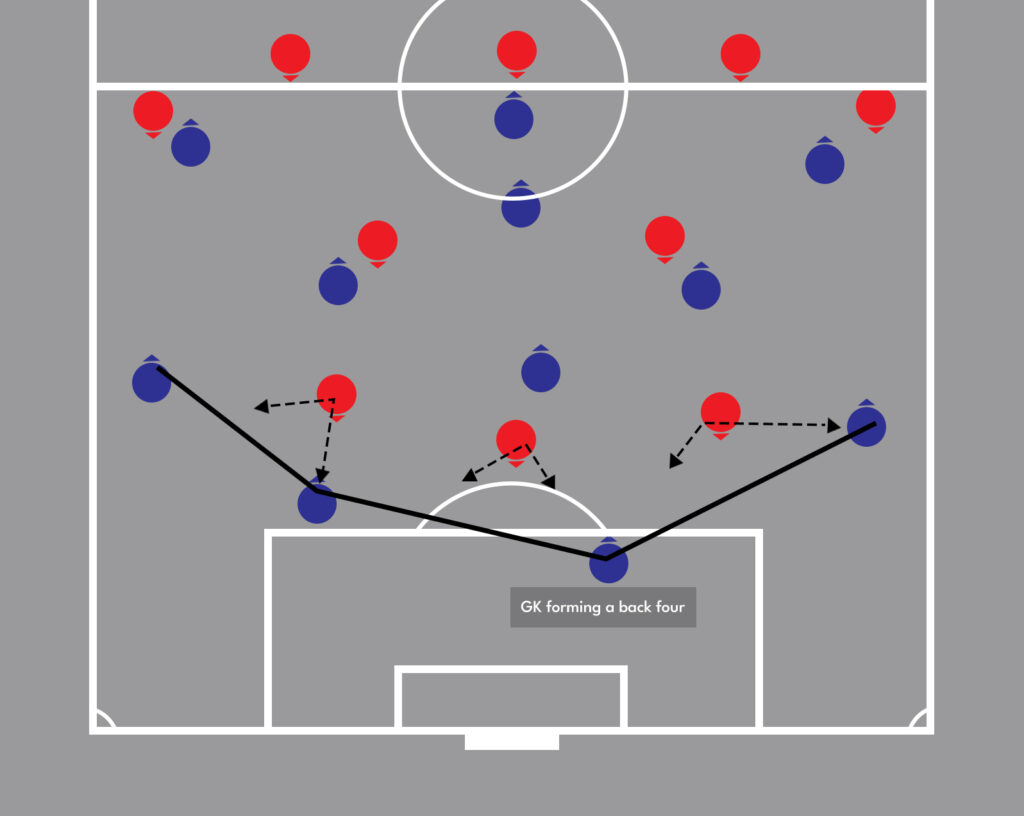

When transitioning from a build-up play excluding the goalkeeper to one that includes the goalkeeper, Sanchéz, instead of sticking to his orthodox position, would come out wide on one of the half spaces inside his own defensive third. This allowed the Brighton back line to adjust their positioning and form a chain of four at the back, incorporating the GK within it, which allowed the wingbacks to push higher up the pitch and pin the opposition back line, deploying more men in between the lines.

This smooth transitioning between the two systems (a back-three and a back-four) allowed the team to progress slowly with minimum physical movement but efficient positional advantages for the ball to move to the players.

Despite the constant chopping and changing of formations and build-up play from the back—both pre-game and in-game—the back-three was Potter’s go-to defensive setup for most occasions. The back three usually operated in an expansive way, normally drifting wider than the 18-yard box and positioned deep to provide a safe passing option to the players in and around the opposition’s first line of press.

This structure forced the opposition strikers and wingers to make a decision on whether to apply pressure on the defensive line or maintain the central compactness to cut out in-field passing lanes in between the lines.

A dilemma would thus be created, with the former decision opening up the pivots roaming in front of the midfield line and stretching the defensive block for the space in between the lines to be used, while the latter allowed the wide centre-backs to drive forward.

It is these finer details on both team and individual levels that made Brighton’s back line and build-up play more than what the system suggested, making it difficult for the opponents to adapt to their forechecking shape.

However, with the increasing emergence of the back-three in recent years, most teams have devised their own ways of pressing against them in variation. Although the defensive system, pressing triggers, and the areas where the defending teams would force the Seagulls into were different, they successfully circumvented the complexities of Potter’s systems by sharing a common characteristic of dealing against the wide centre-backs man-to-man by adequately cutting off passes in between the lines and preparing a structure to press high by committing enough players up front to deny those safer passing lanes across the Brighton back line.

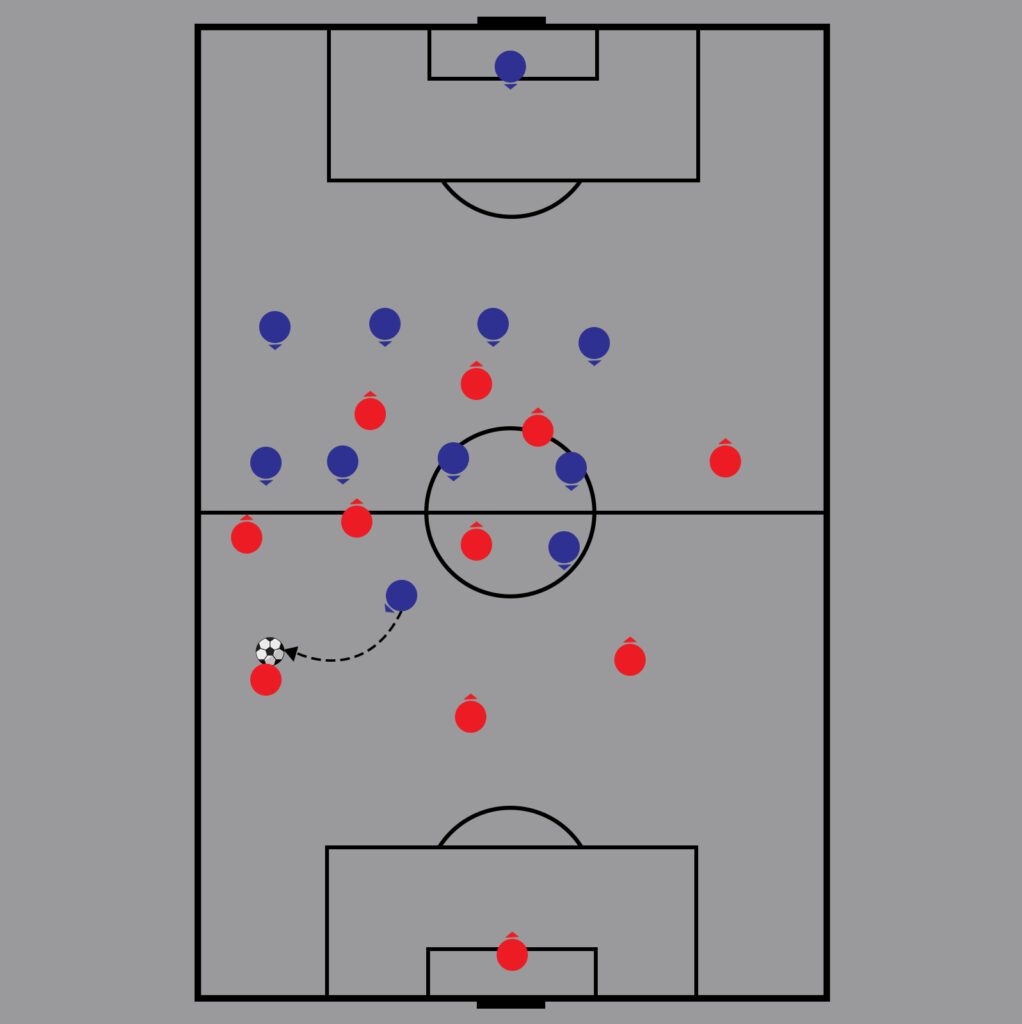

A prime example of this can be taken from Brighton’s home fixture against Everton last season. Everton initially set up in a defensive 4-4-2, setting up a compact structure through the middle to force Brighton’s attack out wide. The back line was allowed to circulate the ball in possession in certain situations. However, once the wide centre-backs started to drive forward due to the central options being closed, Everton’s strikers locked the Seagulls’ attack out wide, just how a full-back gets stuck in a back-four without a free man in between the lines.

Similarly, against rivals Crystal Palace, Patrick Vieira set his team up in a 4-3-3, with the wingers pressing the wide centre-backs while blocking the passing lanes to Brighton’s wingbacks. This resulted in Brighton’s attack ending in a long ball in behind Danny Welbeck or Leandro Trossard, struggling to take control of the game through stabilised build-up play. Since Brighton would have a clear plan when using long balls such as exploiting the space behind the Palace fullbacks, it was crucial for the defending team to not overcommit players when pressing high, given the front three was more than capable of running in behind or receiving the ball in between the lines.

When facing high-pressing teams, the defined-yet-complex positioning of the Brighton fullbacks often attracted the opposition fullbacks, opening space in behind to exploit with attacking options like Marc Cucurella and Tariq Lamptey.

Looking back at the previous and current set of defenders Graham Potter has coached, it is evident that he has developed players capable of playing in multiple positions across the backline. The likes of Benjamin White, Dan Burn, Jöel Veltman, and Marc Cucurella have all played as a centre-back, a fullback, and even a wingback (White also played as a defensive midfielder on numerous occasions). This flexibility on an individual level created adaptability in the back line, enabling easier in-game structural alterations. Throughout last season, the flexibility of their backline allowed Brighton to build up with a back-three that would morph into a back-four when progressing into and attacking in the final third as one of the centre-backs pushed high and wide.

Uniquely profiled defensive midfielders to aid build-up play

Graham Potter’s constant alternation of systems—both pre-game and in-game—would see the defensive midfielders switch from a single pivot to a double pivot and vice versa during the course of a full 90-minute game.

Of the diverse bunch of midfielders Potter had at his disposal since the start of last season — Yves Bissouma, Adam Lallana, Pascal Groß, Alexis Mac Allister, Moises Caiçedo and (sometimes) Steven Alzate — Bissouma will always stand out as Potter’s most trusted deputy, since he was capable of playing both as a lone pivot or part of a double pivot.

In possession, Bissouma had the physical and technical competency to keep the ball in high-pressure situations, helping Brighton secure possession and creating time and space for others to transition to their attacking structure. The force that he would generate when driving forward with the ball is a strength very few in that Brighton setup possessed.

When Bissouma was sold to Tottenham Hotspur at the beginning of this season, Moisés Caicedo stepped up as the pivot in Potter’s new midfield. He provided more line-breaking passes and sustained a similar ball-retention rate as Bissouma with an extremely high lung capacity. He also has the capacity to make forward runs into the gaps between the opposition defenders, always providing the team with an extra man in the middle-third-ball progression phase.

When Brighton were expected to keep more of the ball, players like Mac Allister and Groß, who normally operated high in between the opposition defensive line and midfield line, would be chosen. Thus, although speculative, I believe this will result in someone like Mason Mount dropping into the Mac Allister role due to his quick ball-circulation rate, ability to switch play with minimum touches, and comfort at playing in tight spaces, which is often required when playing against low blocks. Similarly, replicating Groß’s positional awareness and ability to operate anywhere on the pitch should see the likes of Conor Gallagher and Mateo Kova?i? fighting for that other No. 8 role in Potter’s systems, allowing him to become a second pivot as and when a match situation demands it.

It is important to understand that it is these pivots that are the most crucial part of Potter’s systems.

Let’s look at a few possible scenarios: when the defending team set up in a 4-4-2 structure, a single pivot would occupy the gap between the two forwards, while with a double pivot, one would be positioned in similar areas to a single-pivot system with the other player positioned slightly higher up the pitch to pin the midfielders or move wide to receive the ball in the space behind the two strikers.

Whereas, when coming up against a front-three system, the pivot would take up the half spaces between the front-three while having an attacking midfielder drop deep in front of the opposition midfield line to support this structure and create a 3-1-5-1 or a 3-4-3 (diamond) — a common characteristic found in any kind of system Potter implemented at Brighton.

In coordination with the deep backline as mentioned above, the pivot was often allowed to drop in front of the first line of pressure when operating as a double pivot, but not deep enough to be incorporated into Brighton’s own defensive line. This triggered the opposition players in their midfield line to step out of position, resulting in bigger spaces for the players up front to receive.

Besides, the duo also looked to make ball-sided runs, meaning that the near-side pivot would position himself on the ball side and slightly deeper to provide a forward option for the centre-backs, while the far-side pivot would position himself centrally. This resulted in a staggered compact double pivot as a unit, covering two horizontal lanes and two vertical lanes, while providing abundant options to the ball-playing defenders as well as ensuring the security of the defensive structure with sufficient players around the ball.

Once the ball was eventually circulated to the sides, be it the fullbacks, the wingbacks, or dropping attacking midfielders, the pivots would be tasked with providing a lateral passing option to the wide players by receiving the ball through the vertical or horizontal gaps in the defensive team’s structure.

In addition to the back pass route provided by the centre-backs, the option in between the midfield line and the defensive line and a player looking to exploit the spaces in behind saw the wide players get supplied with at least three-to-four passing options at any given time. If the striker(s) were to close down the horizontal passing channels, the centre-backs would open up for continuous ball progression. If the central midfielders stepped out, the players in between the lines would step up as a consequence, and the far-sided double-pivot player would position himself to receive through the structural gaps if the horizontal route was shut down, securing a way out for the wide player depending on the opposition’s reaction.

This wide progression method was a major force in Potter’s Brighton building play from the back, creating overloads to attack down the ball side, or isolating the far side to exploit bigger spaces.

Progression

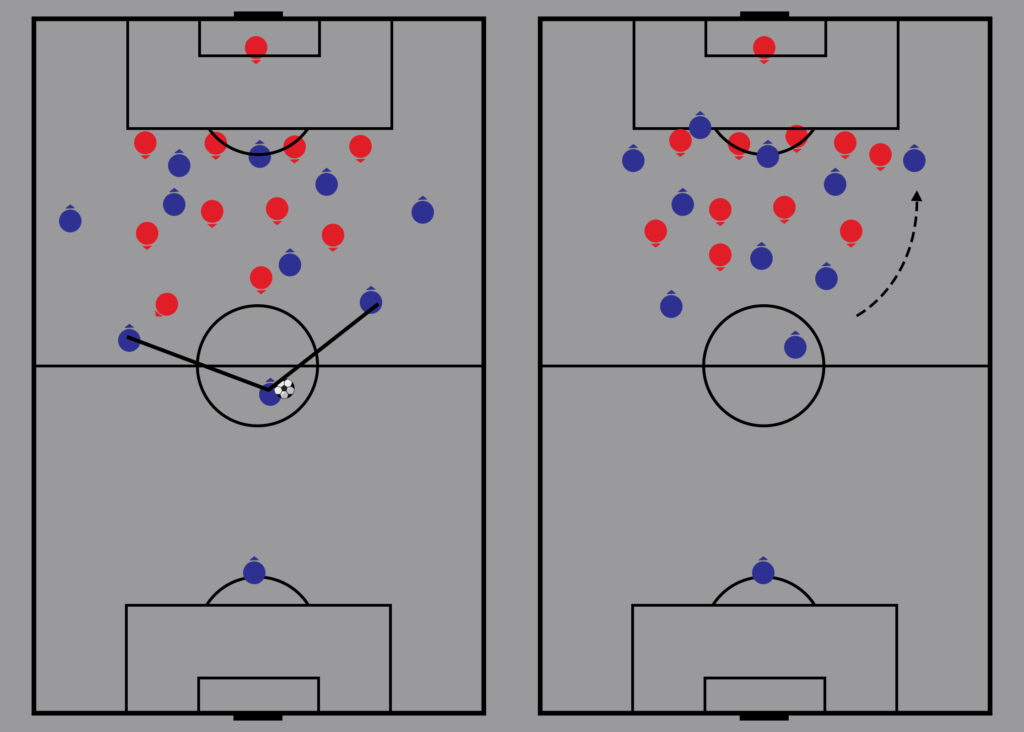

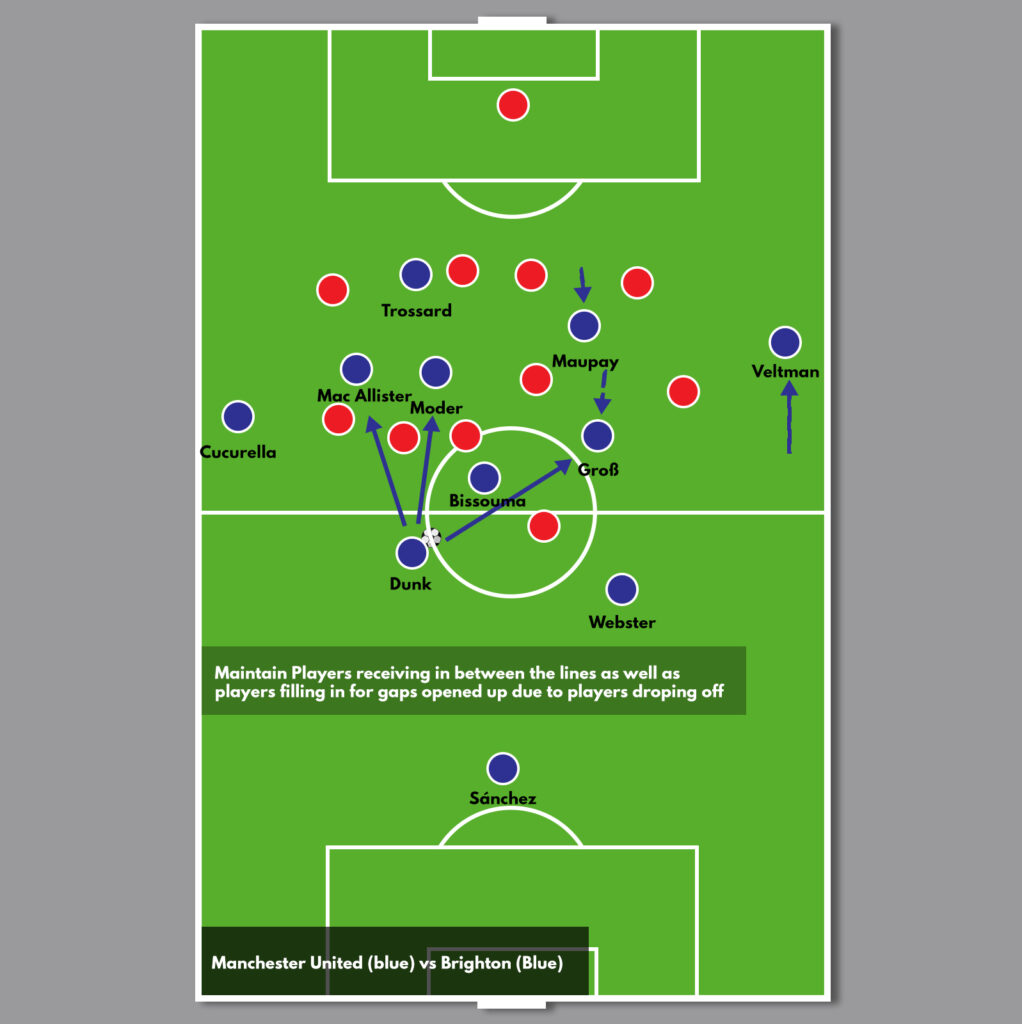

When progressing up the field, Potter’s teams love to take control of the space in between the defensive and midfield lines by overloading that area. It can be crowded to the point of having four players within that confined space, but in an organised manner with a specific discipline so that the players don’t clash with each other.

Pinning the opponent’s backline

It is needless to say that the opponent’s backline has to be pinned accordingly by the players to open spaces in between the lines in order to make it more difficult for the defenders to step out. There were many ways in which Brighton would set up, changing the individual movements the players within each system would make to exploit certain gaps.

One of the most commonly used tactics by Potter was positioning his wingbacks high and wide on the flanks, almost hugging the touchline. They would rarely drift in-field, allowing the central midfielders to roam freely in these areas. In this case, a player dropping into the space between the wingback and the centre-back was one of the most repeated actions to aid Brighton’s ball progression. Not only did it allow them to maintain a sustainable access to the wingback from the centre-back, but it also opened up gaps in between the lines for other personnel to arrive in.

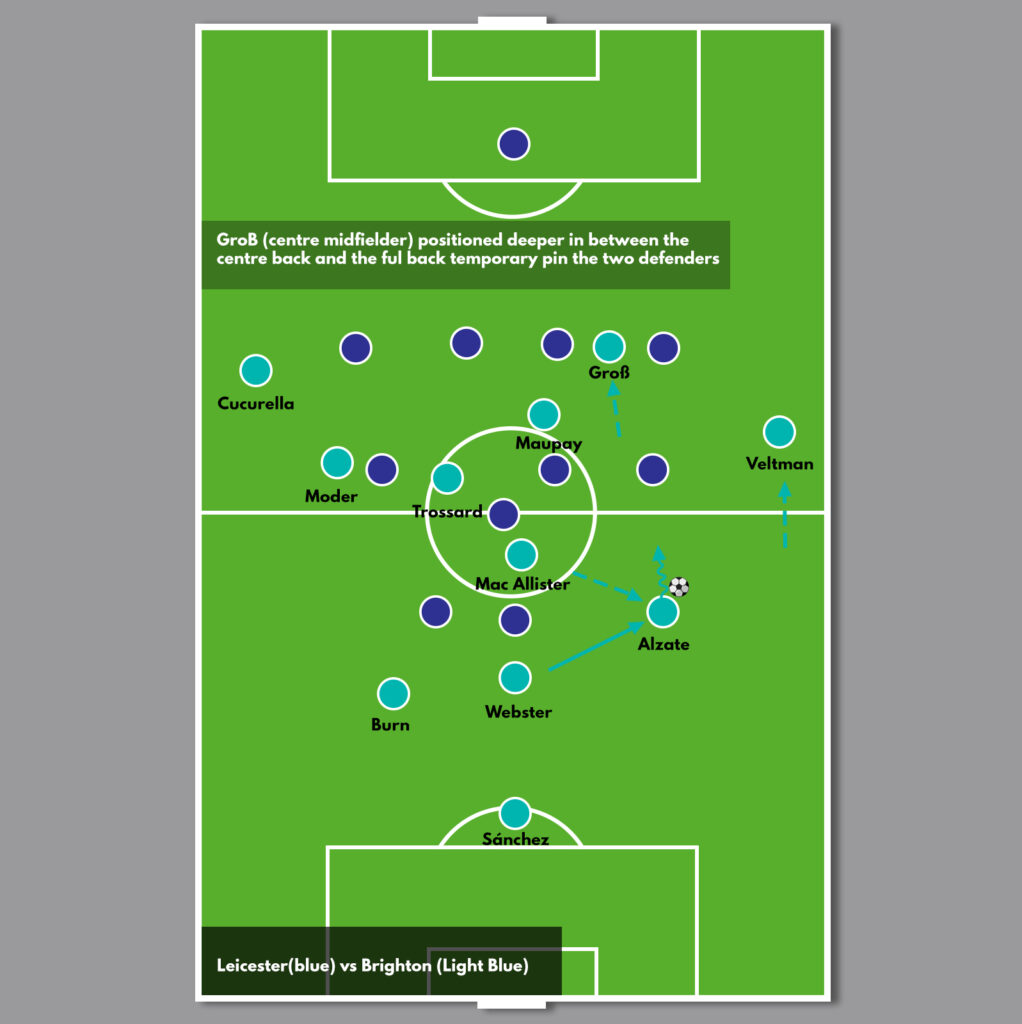

Other notable patterns included the wingbacks sitting deep to support the centre-backs when playing with a back-four, or one that included an attacking midfielder moving slightly higher in between the opposition centre-backs and fullbacks as he’d look to make a darting run out wide from those half-spaces. Similarly, another run in behind would be made if this midfielder was on the far side, attracting the fullback to open up space for the wide player. This positional setup also stopped the opposition centre-backs from applying pressure on the dropping centre-forwards as this movement would open up opportunities for the attacking midfielder (here Pascal Groß) to attack in behind.

The centre-forwards would also cooperate in the pinning process by positioning themselves deep and central in between the centre-backs, working alongside a narrow front-three or fluid structure in between the lines. Penetration in the central area of the pitch was often seen through a player in between the lines moving into the same vertical lane as the deep-lying centre-forward. A horizontal pass through the defensive block from the wide player created a chance of penetration, which was possible due to the deep positioning of both Danny Welbeck and Neal Maupay roaming in between the lines. Additionally, Welbeck, with the capacity to position himself high and wide, usually towards the left-hand side, behaved as a target point for a long ball in behind whilst pinning the defensive line.

When playing with a system of two strikers, they would often position wide and outside of the opposing centre-backs. As mentioned earlier about the central midfielder’s positioning, as they positioned themselves in between the centre-back and the fullback, it allowed Brighton to pin the centre-backs (the two wide centre-backs in a back-three) and the runners to run in behind or wide according to the defenders who were pulled out of position.

Control in between the lines

Once the defensive line would be pinned at the back, Brighton could utilise their numbers in between the lines. Needless to say, all the details described in the previous build-up play section, such as the defensive midfielders attracting the opponent midfielders, also played a part in opening up the targeted spaces.

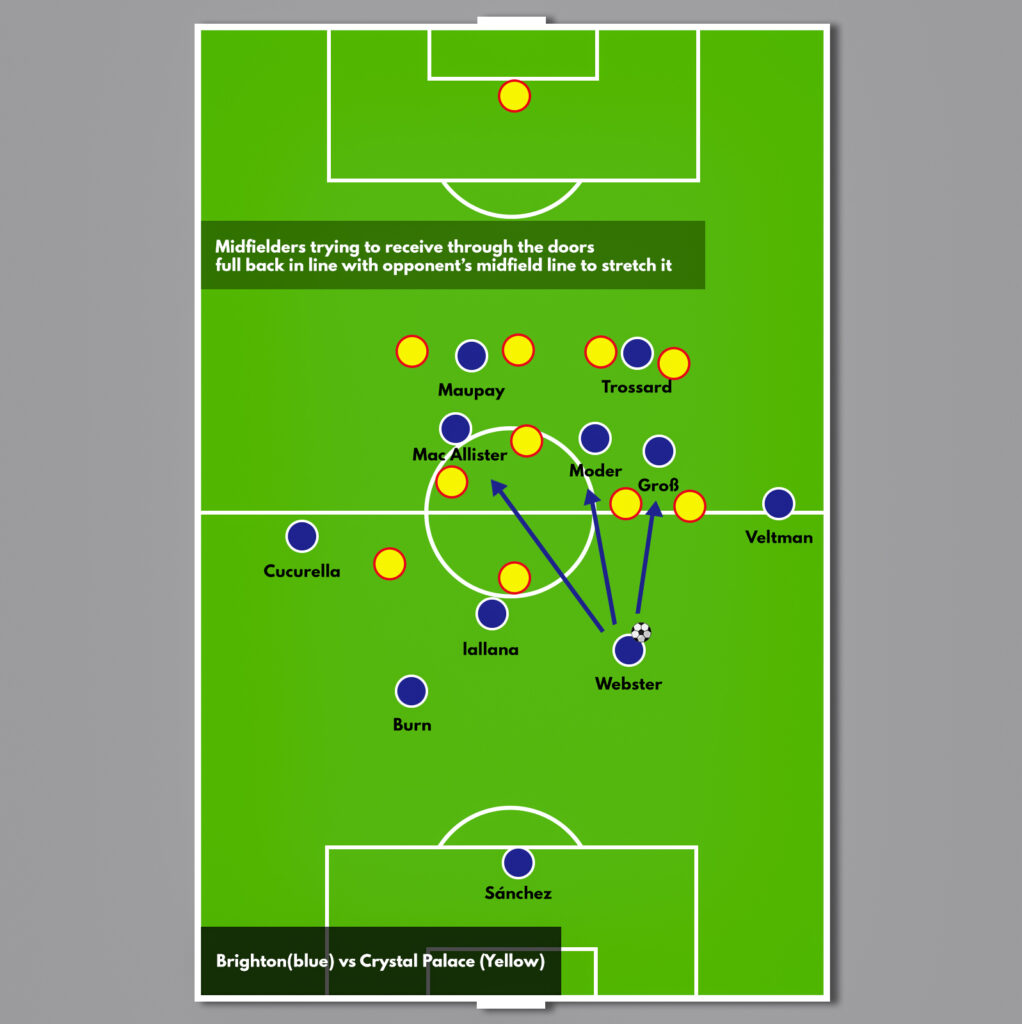

The initial positioning of the players, mostly a striker dropping off or a central or an attacking midfielder dropping in between the lines, would see them operating themselves behind a gap, a “door”, created by two midfielders when the team aimed for central progression.

Additionally, the Seagulls would also try to receive beside the midfield line by altering their positioning slightly wide. Although the combination of these principles was a shared characteristic among all the players trying to receive in between the lines, the “doors” they looked to receive through would depend on the opposition’s defensive structure and the match plan, which had a big impact on their positioning even when they played the same system. The fullback’s positioning in line or just beyond the opposition midfield line aided for the doors to stretch, making the pass in between the lines more successful.

Consequently, fluid rotations in between the lines would form in order to constantly occupy this area and provide support for the wide ball holder.

When analysing some of Brighton’s matches, the wingbacks could frequently be seen making what seems as like a risky horizontal pass in between the lines, where a successful pass resulted in the elimination of more than three or four opponents at once.

In a 3-4-3/3-4-2-1, which ended up being one of Potter’s most used systems, all three players up front had the licence to drop in between the lines. When Maupay (who tends to drop off quite a bit) played as a striker, Brighton would have two high and wide wingbacks to balance out with three players in between the lines. Welbeck as the second striker, on the other hand, provided the structure up front with a different dynamic, usually resulting in a narrow front-three with regards to the more vacant space available due to Welbeck’s deep positioning. Passes between the front-three were made much easier by maintaining a compact structure between them whilst also creating a confusion for the zonally-oriented opposing defenders, as the narrow structure made it more difficult for them to identify who was responsible for marking the front three. Spaces on the far sides were generated as a result, triggering for a defensive midfielder to jump up the field to attack the space if needed.

Another common back-three system used in modern-day football is the 3-1-5-1, quite often implemented by Julian Nagelsmann in the Bundesliga teams he has coached. There are a few ways of describing this, such as the 3-4-3 (diamond), 3-1-3-3, or 3-3-3-1 depending on the perception of the viewers, but with a similar fundamental of a back-three followed by a single pivot which is connected to the three midfielders in between the lines. Width and depth are regularly provided by the deep and wide wingbacks in this system, with the option of the lone striker dropping off, resulting in a pack of four players in between the defensive and midfield lines. Attacking midfielders are instructed to make more movement with the overload in between the lines and open up more spaces around the pivot compared to the traditional 3-4-3.

Despite the risky nature of having only four players at the back and six players up front, which reduces the security of the rest of the defence, it creates more points to place a line-breaking pass and generate a deadlier threat on the opposition as more players are attacking behind the midfield line.

Not only did this system aid Brighton’s progression on the ground but also in the long-ball approach, as the positional superiority the midfielders gained was optimised by a higher chance of collecting the second ball. This trait saw the system being used frequently against the Big Six opponents.

Systems incorporating a back line of four defenders see more variations being put in place as the structure itself affords depth and width to the attack, whilst the back three will always need wide players on each side. More players up front mean different shapes in different positions need to be designed.

Among the back-four systems used by Potter at Brighton, the 4-3-1-2 was his favourite. It can be described as a more attacking system when compared to the 3-1-5-1, as the diamond-shaped midfield would be maintained but a centre-back would be sacrificed for another striker up front. This structure provided as many options in between the lines as a 3-1-5-1 but with more central occupation of the opposing defensive line and a stronger focus on getting past the first line of pressure and stretching the midfield line with low fullbacks to support the centre-backs’ build-up play.

Some other systems were also used in limited capacity, such as the 4-2-3-1 and the 4-3-3. The former of the two served as a midway point between 3-1-5-1 and 4-2-2-2, with a similar structure up front with the lone striker and the three in between the lines. It was also identical to the 4-2-2-2 given that the double pivots provided enough coverage in front of the opposing midfield line, allowing the attacking midfield trio up front to keep roaming around the space in between the lines whilst the back-four remained in place to stretch the midfield line. The latter of the two was one of the unique systems where Brighton used a wide and deep winger alongside the back-four from their initial positioning.

By occupying the areas in between the lines through different systems as described above, the opposition midfielders would end up in a situation where Brighton players tried to receive in behind their backs or move accordingly to support the progression. This led to secure ball possession in the back line due to them not being able to commit and press the Brighton defenders driving forward or the pivots receiving in front of them. Once a defender committed, the player waiting in between the lines would suddenly become available, providing an option to progress forward and accelerate the attack into the final third.

In terms of maximising the positional and the numerical advantage in midfield, numerous fixtures saw Brighton’s back line designed similar to the opponent’s structure up front, meaning that it wasn’t rare for Brighton to keep possession of the ball with a back-three against a 4-3-3, or using a back-four against a 4-4-2. This was done in order to attract opposition up front to open up the midfield area, making sure the back line didn’t just serve the role of creating a spare player at the back line.

Thus, Brighton achieved the overlooked concept of building up and progressing play with the same number of players, pressing the back line with appropriate support, with the opposition back line effectively pinned.

The final third

Wide adaptive triangles

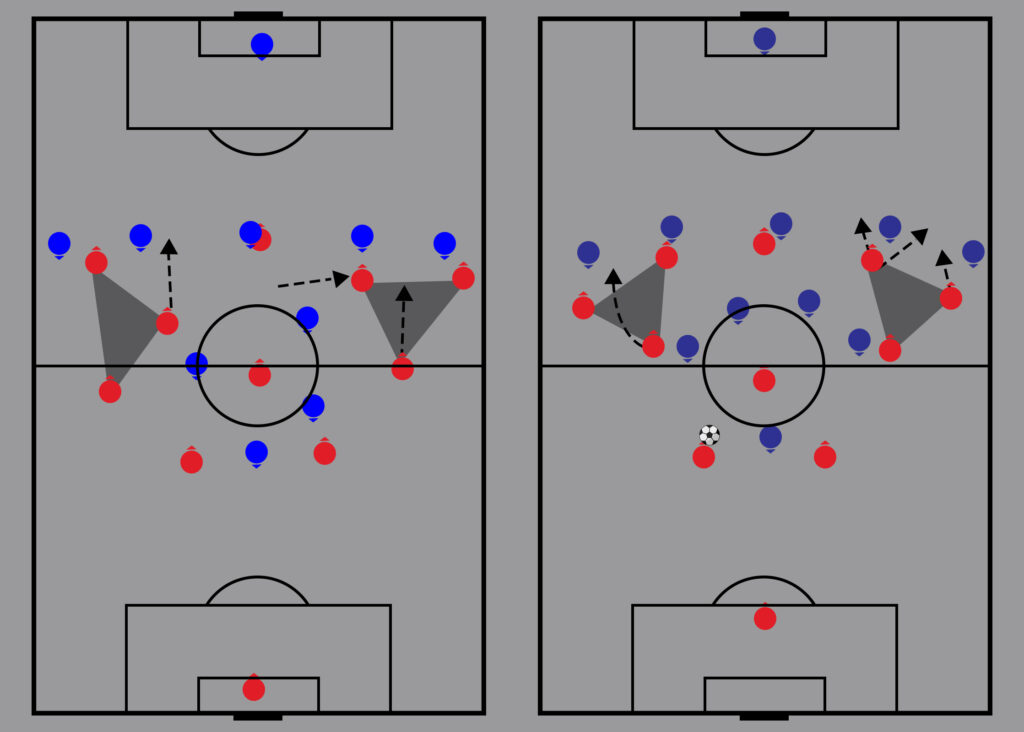

With Potter, Brighton’s progression into the final third tended to end in the wide areas for several reasons, one being the fact that the wide areas provided more successful counter-pressing with the limited angle of options and made the opponent’s counterattacking distance further, the other factor being the pace of Brighton’s attack in the final third.

The slow nature of the attack gave Brighton time to sort out their defensive structure at the back and have a better security of possession to recycle the attack. Interestingly, unlike other teams trying to generate individual moments that could be advantageous in 1v1 situations in the deep and wide positions, the Seagulls would often have players with rather opposite characteristics such as Cucurella, Veltman, Gro? and Jakub Moder, given that these players’ strengths do not lie in their individual quality to drastically change the situation out wide and attract opponents to free up other teammates.

Brighton do have players who can increase the wide 1v1 dominance such as Solly March and Lamptey who played a combined total of just over 30 games last season and ranked in the top five of attempted dribbles for the team. However, they were used as substitutes for half of the matches and lacked the ability to consistently gain individual superiority over Premier League fullbacks, which increased the need for sustainable and reproductive structure to create chances while not being reliant on specific individuals.

On the pitch, this network resulted in the wide triangles Brighton created, including a wide player, a player providing a back-pass option for said wide player, and one who would position himself in front of the gap (door) between the centre-back and the fullback. A player positioning in this pocket could subsequently support the wide ball-holder by receiving through a door created by two wide defenders, which was the main wide progression support in any area in which Brighton held possession. The starting position of these players could be flexible in regards to the situation of the game and the characteristics of the opponents.

The player occupying the pocket could stay in the space to receive if a gap opened, with the opposing defensive line retreating into the box, vacating the space in between the lines. By positioning in the blind side of the defending fullback, a quick horizontal pass could then eliminate the opposition pressure with an immediate chance creation. However, that was not often the case with top-end defensive structures, where they were extremely compact and agile to close down this space.

Therefore, a player in this pocket would look to drop off from the initial position at times and in front of the opposing midfield line, leaving the pocket open for a dynamic occupation of the space. The wingbacks were allowed to make a diagonal run into the pocket, as well as the centre-forward moving across lanes to receive in the space, or even the wide centre-backs underlapping to receive in the pocket and further attack the space behind if necessary.

One last crucial part of the triangle included the player providing a back-pass option for the wide player. This position could be fulfilled by a defensive fullback, the ball-side pivot player, or a wide centre-back, securing a way out for the ball-holding wide player to go back and restart the attack. This player tended to be slightly inverted compared to the wide player, but in a close proximity for quicker counter-pressing to be executed. When in possession of the ball, the player would be surrounded with opportunities of continuous combination within the wide triangle and a central penetration. A lateral passing route would also be provided mainly by the defensive midfielders, usually positioned in between the opposing midfielders and the forwards, in order for an easier switch of play to be performed. Also, when the defensive structure retreated to the point where even the back pass option was marked, the central centre-back in a back-three or the ball-sided centre-back in a back-four would shift his positioning to ensure an emergency option to pass back.

Penetrating the 18-yard box

Potter’s emphasis on attacking down the side in the final third consequently led to more crosses into the box, but Brighton had to do it with physically inferior players compared to the opposition centre-backs. To make the most out of the limited resources, there was a tendency to focus on areas where players made runs into, as well as maintaining a structure on the far side and around the box to minimise the damage from counterattacks. Besides, the movements within the penalty box were nothing out of ordinary, with players aiming for the near post, space behind the opposition fullbacks, and in-between the gap of the defenders.

In terms of the priority of where to make the runs, the strongest emphasis was placed on the near post, with diagonal runs being made there as the player attacking the gap in between the defensive line served the role of pinning the defenders to open up space for others. Welbeck’s physical capability saw him position more on the far side to meet the cross, while small runners aimed for areas closer to the ball.

Due to these runners who got closest to the goal, the defensive line was forced to drop back and opened up space for cutbacks to be made as a result. A popular location for a player to arrive in was the penalty spot and sometimes in the half lane for steeper angle of cutback to be completed. The concept of receiving through the door still remained similar until this area as well.

Around and outside of the box, Potter’s Brighton were known for their strategic distribution of players to allow intensive gegenpressing to be made in case of the loss of possession and for a more secure defence structure. Here, one to three players would usually be placed on the edge of the box in order to fulfil the role of collecting close-range second balls and also establishing a cutback option for the crosser. This area was mainly occupied by the pivot or the centre midfielders, with the option of the wide fullback/wingback and the wide centre-back joining in.

The central midfielders were naturally positioned around this area due to the fact that they had to provide a lateral option for the back pass option in the wide triangles as mentioned previously. In terms of the wide fullbacks/wingbacks, they had to follow the rule of tucking in over to the width of the 18-yard box when the team attacked further into the final third, closing down potential options for opponents to initiate counter attacks from the far side.

Because of this, fullbacks and wingbacks would naturally occupy the edge of the box, the latter getting more chances to attack the space behind the opponent fullbacks. The wide centre-backs, on the other hand, were regularly tasked to follow the forwards with a rather man-marking style of defence which led to them pushing higher up to the area in relation to the opponent’s movement. The structure allowed for better initial contact to be won, which was followed by intensive gegenpressing and press-backs by players up front to regain possession and start over the attack.

Conclusion

Now we know just one or two of the underlying reasons which played a role in Thomas Tuchel getting sacked: not being on the same page as the owner, unwillingness to take the role of a manager and favouritism were just some of the reasons that surfaced in the aftermath of the German’s dismissal.

But, in the field of play, there were three primary issues Tuchel had at Chelsea:

- It was the two wingbacks who were holding the width in the attacking third, whereas in elite teams at least one winger holds the width.

- Pressurising the ball when pressing against a four-at-the-back team due to the distance the wing-backs had to cover.

- The front three lacked in quality.

Graham Potter, in his first game in charge of Chelsea, tried to solve these issues by:

- Fielding Raheem Sterling wide in the 3-4-3 on-the-ball shape.

- By setting up in a 4-4-2 out of possession to have more numbers high up the pitch to press.

- Switching the front-three to a front-four so that there would be less reliance on individual quality.

And with the players that he had picked, it was perceived that Potter’s Chelsea would play in a 3-4-3/4-4-2 system. These are the same principles Pep Guardiola uses at Manchester City.

Moreover, the thing is, the staples of quality in Tuchel’s 3-4-3 still remain. Chelsea would still be ultra-compact in defensive transitions due to the spacing in the final third and the presence of a double pivot. They’d still be in close proximity to combine and create. Same philosophy, but still improved. At least on paper.

As predicted, Chelsea started the game with their 3-4-3 on-the-ball and 4-4-2 off-the-ball structures, where Mason Mount took the right half-space on the ball and moved to the right of a 4-4-2 when off the ball, while Kai Havertz operated on the left half-space on the ball but moved alongside Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang when off the ball.

However, when Potter decided to start with the duo of Mateo Kova?i? and Jorginho, it was believed that he’d go with a double pivot in midfield. But as the game progressed, Kova?i? started roaming a lot more, making Chelsea’s structure look more akin to a 3-1-3-3 at times, with Jorginho at the base, Kova?i? on the left half-space, Mount on the right half-space, Sterling and Reece James holding the width, and Havertz roaming in between the lines behind Aubameyang. That’s too fluid.

It is not something that can’t work, of course; it can. But football is always made easier for players when positional rigidity is maintained and there is fluidity within that. When Kova?i? moves to the left half-space, Havertz is often drifting into a no-man’s land. A better alternative is Kova?i? sticking to the single or double pivot role, which would allow Chelsea to have constant occupation of the half-spaces with both Mount and Havertz pinned in there for the likes of James and Sterling to combine with. This would also allow players like Cucurella, César Azpilicueta or any of the pivots to make runs from deep as Chelsea sustained attacks.

The one thing that I truly disliked about Potter’s tactics from his first game in charge of Chelsea was the midfield three accompanied by split centre-forwards. Most of the traits and strength of his system were crippled when he decided to start Kova?i? in that No. 8 role and Jorginho as the No. 6 instead of them playing as a duo. This left very little room for combination on the sides or access to the split centre-forwards, resulting in Mount and Kova?i? often standing in the same line as Aubameyang and Havertz, inadvertently blocking access to them.

Besides, when James and Sterling received the ball they missed the presence of a spare man to combine with, as they were dependent on the two No. 8 midfielders who were making the runs from deep instead of being staples in the half-spaces. The only instance where Chelsea effectively created anything of substance was when Cucurella pushed forward on the outside or on the back of a transition. There should always be constant occupation of the key zones so that combinations can be reliable, but they weren’t.

Thus, Potter did not give Chelsea the best possible chance of winning. He gave them a structure and a decent chance, but it was not optimal enough to see them through. They struggled to create chances because the attack was too fluid. The solution? Putting Kova?i? in a double pivot for rigidity.

Since at this point in time making the top four will be more important than anything else, the best solution for Potter will be to attack in a 3-4-3 and defend in blocks of 4-4-2. Forget the 3-1-3-3 for a second, for there’s no reliable combination play or anything of sorts in that system. It’s too fluid, and the lack of positional rigidity results in the players having little to no reliable options to combine with. The base is there, but it needs massive improvements all across the board.

This is how Guardiola, Jürgen Klopp, Mikel Arteta and Erik ten Hag’s teams operate, and they have showcased the blueprint as to how to be the best. Potter has to follow this to the tee, and it definitely looked like he was going that route pre-game before he decided on starting Jorginho as the No. 6 and Kova?i? as one of the No. 8 mids.

The 3-4-3/4-4-2 system is the way forward for Potter and Chelsea, and not the overly fluid 3-1-3-3. That doesn’t cut it from a structural perspective for any sort of team. Potter, however, as we’ve come to know him, loves to change systems, and that will likely happen in the coming weeks to improve upon this. His biggest drawback, however, is also this knack of too much chopping and changing. This will more likely lead them to cup success in the short to medium term, but this approach will most likely see Chelsea underperform in the league big time.

While one can get away with different systems for every other game in a mid-table team, the stakes are much higher at a club like Chelsea and the margin for error is minuscule. And while I have no doubts about his coaching methods or his ability to identify talent, Potter’s in-game tactics and fluidity of systems put a big old question mark against his name until proven wrong.